By Nathan Cemenska

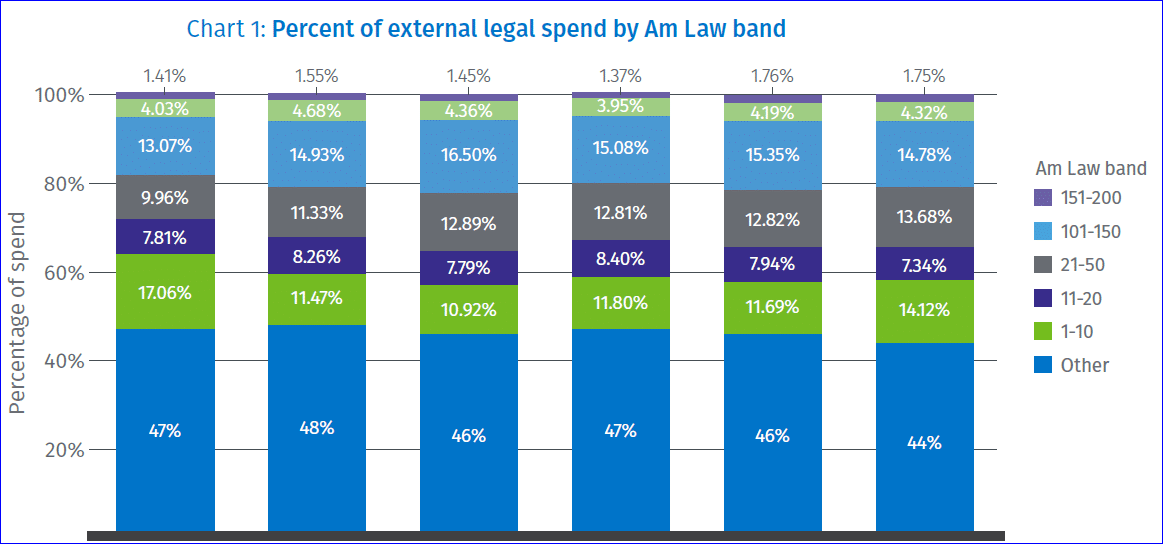

A recent analysis out of LegalVIEW—the largest body of legal performance data in the world—indicated that Am Law 50 firms tended to gain market share from 2019 to 2020, whereas unranked firms lost it (see below chart). This shift reinforces earlier observations about a “flight to quality” in the legal profession, where clients do more and more business with the largest, most prestigious firms and less business elsewhere. And early reports on 2020 firm performance agree, indicating the top 50 firms grew revenue by 7.1 percent, while the Am Law 50-100 experienced only 2 percent growth.

However, the phrase “flight to quality” is somewhat misleading because the legal industry has never defined quality, let alone measured it. Therefore, any assertion that legal work is “flying to quality” cannot be evidence-based. The change is better characterized as a “flight to prestige,” and this points to an embedded industry assumption that prestige = quality. Unable to verify the services they are paying millions for are quality, CLDs do what leading management theorist Clay Christensen claimed purchasers of consulting services do: They buy based not on quality, but proxies for quality, including “educational pedigrees, eloquence, and demeanour.”

I’m not saying the “flight to quality prestige” is bad for quality since there is scant evidence either way. And regardless of quality, there are other reasons to move work to larger firms. For instance, the ongoing trend of converging more and more work into fewer and fewer suppliers necessitates the use of larger firms with greater ability to scale in terms of both geography and practice area. Continuing law firm mergers also drive the “flight to quality prestige,” as lesser-known firms get acquired and become part of larger, more prestigious entities. And more and more law departments are prohibited by internal information security requirements from dealing with smaller firms that cannot or will not lay out the money to comply.

Despite these reasons to use more prominent law firms, there are equally good reasons to think the “flight to quality prestige” is unnecessary, even counterproductive. Many of the leading thinkers in the legal profession – including Bill Henderson, Mark Cohen, Jens Nasstrom, Evan Parker, Marjorie Shultz and Sheldon Zedeck – question whether there is as much of a relationship between prestige and quality as law firms would have their clients believe.

Parker, in particular, has spent much of his career using statistics to predict whether – after leaving the bubble of academia – a young lawyer will be successful in practice. His work is so provocative that it got the attention of Malcolm Gladwell, who interviewed him. In the interview, Parker said, “It really does not matter at all” where you went to law school. On the other hand, having served in the military, worked a blue-collar job, or played varsity sports were all indicators that a particular candidate was more likely to thrive as a practicing attorney, all else equal. So why the continued pedestalization of law review membership and grades? Parker believes it is because the legal profession is not the meritocracy it claims to be but a “mirror-tocracy.” He told Gladwell, “You end up selecting people who are like you, not people who are like the successful attorneys at your firm.”

Parker’s research is about law firms hiring new associates, not about CLDs hiring law firms. Still, the insight carries over: Law firms pedestalize prestige in hiring associates, and purchasers of legal services pedestalize prestige in hiring law firms. Meanwhile, the fact that quality isn’t measured or managed allows sourcing decisions to come down to squishy factors that probably shouldn’t matter.

What would CLD buying behavior look like in a world that emphasized results, not prestige? Well, it might look something like the insurance claims market. Claims departments pay for results, not prestige, and are a decade or two ahead of corporate law departments in making their sourcing genuinely evidence-based. They meticulously collect data on case length, attorneys fees and settlement amounts and hire based on those factors. Furthermore, the last few years have seen more and more of them using artificial intelligence like Wolters Kluwer’s Predictive Insights to further optimize their firm selection. One of the factors AI doesn’t care about: prestige.

But claims departments go even further, eschewing large, expensive firms with high overhead in favor of a vast, geographically distributed network of small firms and even solo practitioners who—despite having little or no prestige—continue to hit the performance targets their clients expect. The reasons for this distributed model are somewhat incidental and beyond the scope of this article, but in a post-pandemic world, it makes more sense than ever now that we realize physical offices and geographic location aren’t necessarily relevant.

Big Law leaders will claim that while small firms can handle average, regional claims litigation, they do not have the required resources to handle more complex work. Smaller firms, they claim, do not have the IT people and infrastructure, the eDiscovery and document review teams, and the scores of memo-writing junior associates necessary to avoid being overwhelmed. It’s a fair point, but the people making it look for problems while the creative claims people are looking for solutions.

For instance, an industry-leading insurer with which my company works recently purchased hundreds of licenses for a cutting-edge AI-assisted litigation brief-writing product and gave its entire network of defense lawyers access. Those attorneys now have an unfair advantage that most of their competition—the largest firms included—would envy. Likewise, insourced or ALSP e-discovery teams can be put at the disposal of a distributed network, giving smaller firms the ability to punch well above their weight.

Will the above model become so powerful that it makes BigLaw obsolete? Not any time soon. The industry is going in the opposite direction – perhaps due to lack of perception or perhaps due to inertia. But in the meantime, supporters of evidence-based legal practice are quietly building a case that may very well end up shattering the “mirror-tocracy.”

About the author: Nathan Cemenska, JD/MBA, is the Director of Legal Operations and Industry Insights at Wolters Kluwer’s ELM Solutions. He previously worked in management consultancy helping GCs improve law department performance and has prior experience as a legal operations business analyst. In past lives, Nathan owned and operated a small law firm and wrote two books about election law. He holds degrees from Northwestern University, Ohio State University, and Cleveland State University.

Comment: BigLaw – Does prestige equal quality? Does it have to?

Comment: BigLaw – Does prestige equal quality? Does it have to?

By Nathan Cemenska

A recent analysis out of LegalVIEW—the largest body of legal performance data in the world—indicated that Am Law 50 firms tended to gain market share from 2019 to 2020, whereas unranked firms lost it (see below chart). This shift reinforces earlier observations about a “flight to quality” in the legal profession, where clients do more and more business with the largest, most prestigious firms and less business elsewhere. And early reports on 2020 firm performance agree, indicating the top 50 firms grew revenue by 7.1 percent, while the Am Law 50-100 experienced only 2 percent growth.

However, the phrase “flight to quality” is somewhat misleading because the legal industry has never defined quality, let alone measured it. Therefore, any assertion that legal work is “flying to quality” cannot be evidence-based. The change is better characterized as a “flight to prestige,” and this points to an embedded industry assumption that prestige = quality. Unable to verify the services they are paying millions for are quality, CLDs do what leading management theorist Clay Christensen claimed purchasers of consulting services do: They buy based not on quality, but proxies for quality, including “educational pedigrees, eloquence, and demeanour.”

I’m not saying the “flight to quality prestige” is bad for quality since there is scant evidence either way. And regardless of quality, there are other reasons to move work to larger firms. For instance, the ongoing trend of converging more and more work into fewer and fewer suppliers necessitates the use of larger firms with greater ability to scale in terms of both geography and practice area. Continuing law firm mergers also drive the “flight to quality prestige,” as lesser-known firms get acquired and become part of larger, more prestigious entities. And more and more law departments are prohibited by internal information security requirements from dealing with smaller firms that cannot or will not lay out the money to comply.

Despite these reasons to use more prominent law firms, there are equally good reasons to think the “flight to quality prestige” is unnecessary, even counterproductive. Many of the leading thinkers in the legal profession – including Bill Henderson, Mark Cohen, Jens Nasstrom, Evan Parker, Marjorie Shultz and Sheldon Zedeck – question whether there is as much of a relationship between prestige and quality as law firms would have their clients believe.

Parker, in particular, has spent much of his career using statistics to predict whether – after leaving the bubble of academia – a young lawyer will be successful in practice. His work is so provocative that it got the attention of Malcolm Gladwell, who interviewed him. In the interview, Parker said, “It really does not matter at all” where you went to law school. On the other hand, having served in the military, worked a blue-collar job, or played varsity sports were all indicators that a particular candidate was more likely to thrive as a practicing attorney, all else equal. So why the continued pedestalization of law review membership and grades? Parker believes it is because the legal profession is not the meritocracy it claims to be but a “mirror-tocracy.” He told Gladwell, “You end up selecting people who are like you, not people who are like the successful attorneys at your firm.”

Parker’s research is about law firms hiring new associates, not about CLDs hiring law firms. Still, the insight carries over: Law firms pedestalize prestige in hiring associates, and purchasers of legal services pedestalize prestige in hiring law firms. Meanwhile, the fact that quality isn’t measured or managed allows sourcing decisions to come down to squishy factors that probably shouldn’t matter.

What would CLD buying behavior look like in a world that emphasized results, not prestige? Well, it might look something like the insurance claims market. Claims departments pay for results, not prestige, and are a decade or two ahead of corporate law departments in making their sourcing genuinely evidence-based. They meticulously collect data on case length, attorneys fees and settlement amounts and hire based on those factors. Furthermore, the last few years have seen more and more of them using artificial intelligence like Wolters Kluwer’s Predictive Insights to further optimize their firm selection. One of the factors AI doesn’t care about: prestige.

But claims departments go even further, eschewing large, expensive firms with high overhead in favor of a vast, geographically distributed network of small firms and even solo practitioners who—despite having little or no prestige—continue to hit the performance targets their clients expect. The reasons for this distributed model are somewhat incidental and beyond the scope of this article, but in a post-pandemic world, it makes more sense than ever now that we realize physical offices and geographic location aren’t necessarily relevant.

Big Law leaders will claim that while small firms can handle average, regional claims litigation, they do not have the required resources to handle more complex work. Smaller firms, they claim, do not have the IT people and infrastructure, the eDiscovery and document review teams, and the scores of memo-writing junior associates necessary to avoid being overwhelmed. It’s a fair point, but the people making it look for problems while the creative claims people are looking for solutions.

For instance, an industry-leading insurer with which my company works recently purchased hundreds of licenses for a cutting-edge AI-assisted litigation brief-writing product and gave its entire network of defense lawyers access. Those attorneys now have an unfair advantage that most of their competition—the largest firms included—would envy. Likewise, insourced or ALSP e-discovery teams can be put at the disposal of a distributed network, giving smaller firms the ability to punch well above their weight.

Will the above model become so powerful that it makes BigLaw obsolete? Not any time soon. The industry is going in the opposite direction – perhaps due to lack of perception or perhaps due to inertia. But in the meantime, supporters of evidence-based legal practice are quietly building a case that may very well end up shattering the “mirror-tocracy.”

About the author: Nathan Cemenska, JD/MBA, is the Director of Legal Operations and Industry Insights at Wolters Kluwer’s ELM Solutions. He previously worked in management consultancy helping GCs improve law department performance and has prior experience as a legal operations business analyst. In past lives, Nathan owned and operated a small law firm and wrote two books about election law. He holds degrees from Northwestern University, Ohio State University, and Cleveland State University.

Recent Posts

In brief: Elevate acquires Legadex

Litera gets into the agentic AI game with formal Lito launch

Legal IT Latest: Tessaract raises £4.6m Series A, Integreon hunts for CEO, BakerHostetler partners with vLex + more

Ilona Logvinova joins HSFK as global chief AI officer

Webinar: 30 years of legal tech – Building AI confidence from a stable foundation

Related

In brief: Elevate acquires Legadex

Litera gets into the agentic AI game with formal Lito launch

Legal IT Latest: Tessaract raises £4.6m Series A, Integreon hunts for CEO, BakerHostetler partners with vLex + more

Ilona Logvinova joins HSFK as global chief AI officer

Webinar: 30 years of legal tech – Building AI confidence from a stable foundation